As catchy as the title sounds, keep in mind that it’s not technically about increasing metabolism per se—it’s about allowing it to function optimally without clogging it up through suboptimal diet and lifestyle choices, which I’m discussing below.

Metabolism isn’t just about burning calories or increasing our basal metabolic rate (although I provide a few tips on that, too). This is about something far more important—preventing metabolic dysfunction.

To encourage long-term optimal metabolic health, doing nothing but following the five recommendations below will not only set you up for success today; it will also prepare you to have a metabolic advantage for decades to come.

What not to do: Rely on body weight as a measure of metabolic health

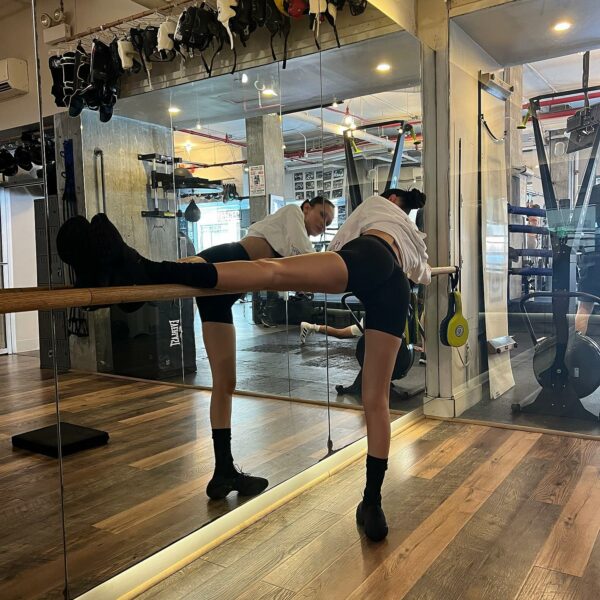

It’s about body composition: the more muscle mass you have, the better.

No matter how many articles you read about specific foods that “increase” metabolism (you know what I’m talking about—cayenne pepper, ice-cold water, etc), they pale in comparison to the single largest factor influencing basal metabolic rate: lean body mass.

Adipose/fat tissue has a lower energetic expenditure compared to skeletal muscle. In other words, the more muscle you have, the more calories you will burn at rest, period.

More importantly, the more muscle mass you have, the greater glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity you will have, and the more metabolically healthy you will be.

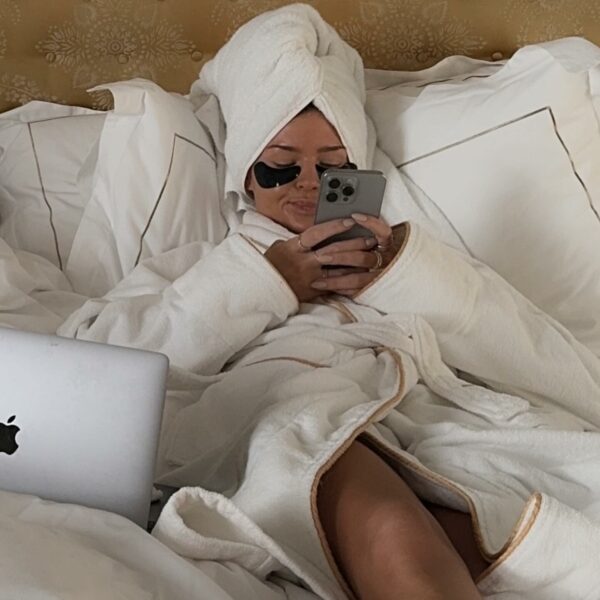

What not to do: Burn the midnight oil

Sleep deprivation won’t get you ahead.

Chronic sleep deprivation has many negative downstream impacts, having both direct and indirect effects on metabolism—those that involve hormone signaling, eating behavior, and even rates of fat loss.

For example, the hormones leptin and ghrelin, which affect our hunger and appetite, are deranged after sleep deprivation. This results in a greater likelihood that we will be eating calorically dense, high carbohydrate foods (the very outcome that’s been shown in research). We don’t always think of hunger hormones as being powerful regulators, but they work together in an orchestra, not in isolation—if one is off, it affects the whole system.

It’s also been shown that even after one week of sleep deprivation, perfectly healthy people can appear pre-diabetic. That’s because sleep deprivation impairs insulin signaling and affects how our body clears glucose. For anyone even remotely interested in keeping metabolic function at its peak, the amount of hours you dedicate to sleep is worth keeping tabs on.

What not to do: Eat around the clock

The timing of food intake affects how our metabolism processes calories.

Our circadian system orchestrates metabolism in a 24-hour cycle, giving rise to rhythms in energy expenditure, appetite, insulin sensitivity, and glucose disposal, as well as other metabolic processes. Many of these processes, including insulin sensitivity and the thermic effect of food (the increase in metabolic rate after ingestion of a meal), peak in the morning or around noon, and plummet late at night.

Increasing evidence in human studies has shown that eating out of sync with these circadian rhythms (by eating during the biological night) promotes weight gain and metabolic dysfunction.

Conversely, eating in sync with our innate circadian rhythms appears to reduce body weight and improve metabolic health. To align your intake accordingly, I recommend having all your food within an eight– to 10–hour window (greater benefit is observed when this window starts earlier in the day, rather than later).

What not to do: Assume all calories are created equal

Just like food timing influences how your metabolism processes energy, the actual source of calories matters too.

What happens when you put suboptimal fuel into a supercar built for performance, like a Lamborghini? Probably nothing.

What happens when you do this for months? For years? It’s simple—the engine will not run efficiently, and that’s going to cause problems down the road.

The same applies to our metabolism. Biology works in averages: an occasional ice cream sundae doesn’t cause problems. But it will certainly cause problems if you start eating that sundae most days of the week.

Rather than hyper-focusing on the “best” source of calories, here’s the big picture: the further you move away from the standard American diet (appropriately abbreviated as SAD), the better for metabolic functioning. This diet is characterized as having high amounts of packaged foods, refined grains, red meat, processed meat, fried foods, sweetened beverages, and sweets. These foods are infinitely abundant, cheap, hyper-palatable, and easily transportable: it’s why you can find them anywhere and everywhere. Remember, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with enjoying something from this list—rather, the fault comes down to eating these foods in excess, and letting them otherwise take the place of whole, nutrient-dense foods.

What not to do: Be sedentary

Sedentary behavior is bad news if you want a high-functioning metabolism.

Sedentary behavior not only becomes a slippery slope, but it can also cause a feedback loop that results in the progressive decline in metabolic function. First, sedentary behavior is oftentimes synonymous with excess energy/caloric intake—both of which negatively influence body composition through increased fat mass and loss of muscle mass (as you learned above, we want the inverse for optimal metabolism and high resting metabolic rate). This loss of muscle mass results in reduced calorie burn and reduced capacity for glucose uptake/energy utilization. This isn’t an exhaustive list of all the mechanisms at play, but collectively, it paints the picture of the reciprocal relationship between muscle mass and metabolic homeostasis.

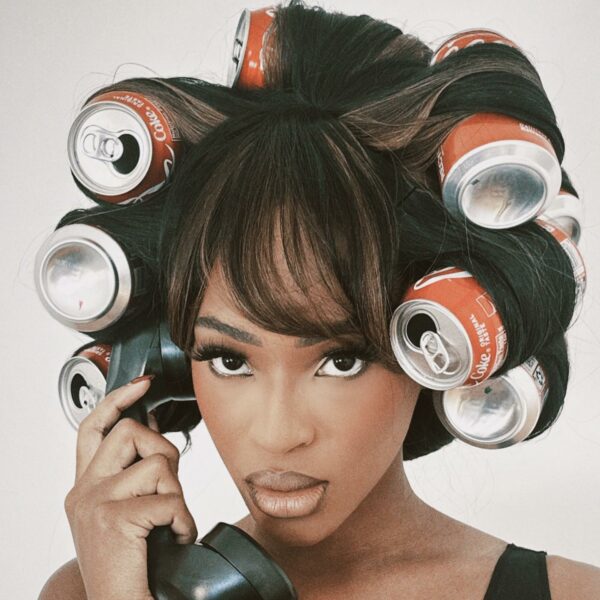

Add extra movement into your day whenever possible, and start small if needed. Take the stairs, get an adjustable standing desk, pace around while talking on the phone. All of these things, even small fidgeting movements (discussed previously), do add up.

Shop our daily supplements collection:

Rachel Swanson, MS, RD, LDN, is a registered dietitian and founder of the nutrition consulting practice Diet Doctors, LLC. She counsels celebrities, C-suite executives, professional athletes, and entrepreneurs as the Nutrition Director for LifeSpan Medicine. Her work focuses on developing personalized treatment plans for cardiometabolic health, longevity practices, weight loss, disease prevention, and optimal maternal-fetal outcomes.

The content provided in this article is provided for information purposes only and is not a substitute for professional advice and consultation, including professional medical advice and consultation; it is provided with the understanding that Poosh, LLC (“Poosh”) is not engaged in the provision or rendering of medical advice or services. The opinions and content included in the article are the views of the author only, and Poosh does not endorse or recommend any such content or information, or any product or service mentioned in the article. You understand and agree that Poosh shall not be liable for any claim, loss, or damage arising out of the use of, or reliance upon any content or information in the article.

Up next, be the first to know our weekly content and sign up for our Poosh newsletter.